How did the African collection end up in the basement?

After twenty years in the British Museum’s basement, Africa is due to be given greater prominence by a new initiative announced this month. But how did the African collection end up underground in the first place?

When the Sainsbury African Galleries opened at the British Museum in 2001, they received a mixed reception. Graham Greene, the Chair of Trustees at the time, had announced that the continent of Africa should hold a central position within the museum, and described the galleries as lying within the Great Court. But the galleries weren’t sheltered by Norman Foster’s iconic glass dome. Instead, they were located beneath the court in what has been disparagingly referred to as a basement. When I first visited, I couldn’t help but notice the unfortunate parallels with racist notions of sub–Saharan Africa as the “dark continent”.

This month, twenty years after the African Galleries opened, the museum has announced a new initiative called “Reimagining the British Museum”. For the Director, Hartwig Fischer, this two-year project will “give greater prominence to Africa”, as well as the collections from the Pacific and the Americas. While the African Galleries are currently on a separate floor from the other geographical collections, the initiative will also “make it easier to understand the connections between different cultures, both ancient and modern”.

But in order to repair the damage done, we must first understand how the collection ended up in its current subterranean location by looking back over the position of African objects throughout the museum’s history.

African objects have been part of the British Museum since it was established in 1753. They formed part of the founding bequest given by physician and slave owner Hans Sloane, whose bust was removed from its pedestal and placed in a cabinet at the museum last summer.

From the outset clear hierarchies were created, with objects being classified into separate categories or taxonomies. Egyptian artefacts were seen to originate from a great “civilisation”, and were therefore separated from other African objects which were considered primitive and labelled as “miscellanies”. By 1808, miscellanies had been reclassified as “modern artificial curiosities”, and, in a telling precursor to the current African Galleries, the majority were stored in the basement.

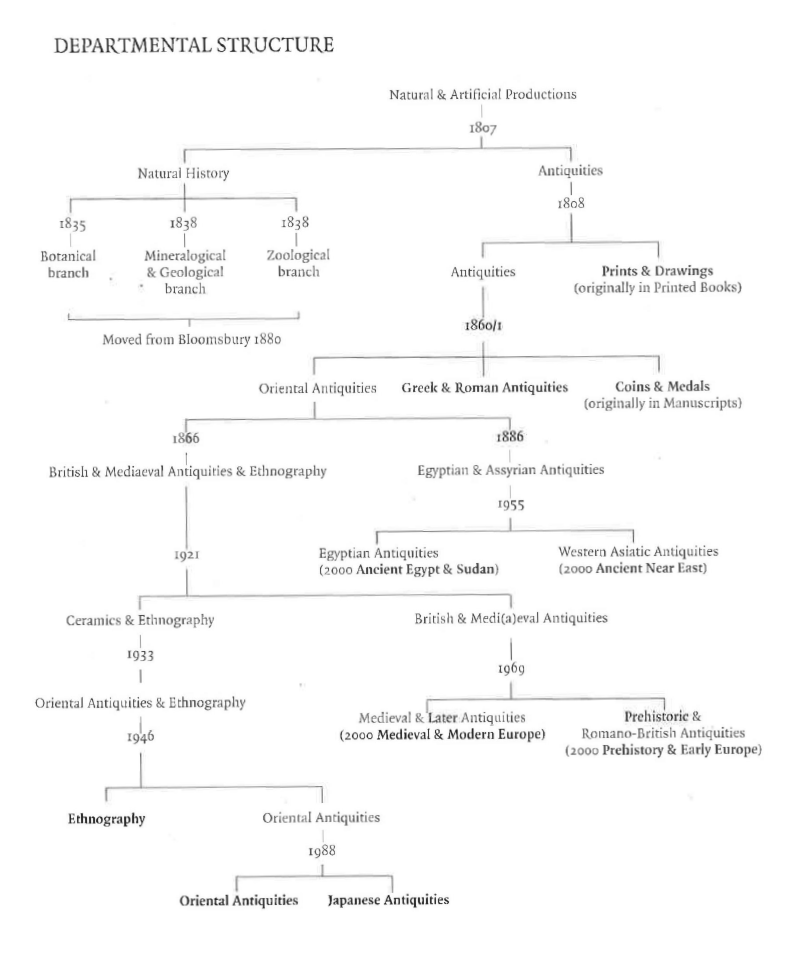

The idea of an ethnographic collection was invented in the 19th century, leading to a further reclassification, this time as “ethnographic objects”. Even when not physically separated from the rest of the museum, the African collection, along with the rest of the ethnographic collection, was still often relegated to the status of sub-department. The objects moved from being an addendum to the Department of British and Mediaeval Antiquities and Ethnography, to the bizarrely configured Department of Ceramics and Ethnography, before the Department of Ethnography was eventually founded in 1946. Throughout this time, “ethnographic objects” were not deemed a priority and were often victims of budgetary constraints.

While the Ethnography Department was considered a cross-cultural department and reportedly did contain objects from parts of Europe, I have found it surprisingly difficult to identify any in the museum’s guides and publications. In a British Museum guide book published in 1879, the Ethnographical Room is described as strictly displaying objects “belonging to all nations not of European race”. A more recent museum publication from 1989 stated that eight of the museum’s departments, including the Ethnography Department, were titled because of “the cultures they study and display”. The other departments listed all refer to geographical areas, whereas ethnography seems to denote a certain “type” of culture which was not highly valued by the museum.

By 1970, the museum was running low on space and decided to relocate the entire Ethnography Department to Burlington Gardens, forming the Museum of Mankind (1970-1997). The collection remained there for almost thirty years, before returning to the British Museum’s main site at Bloomsbury.

Today, like many museums across Europe, the British Museum has ostensibly abandoned the term “ethnography”, reclassifying the majority of the Ethnography Department as the Department of Africa, Oceania and the Americas (AOA) in 2004. According to Brian Durrans, who had worked in the Department of Ethnography since 1976, the vast geographical scope of the AOA Department was a result of none of the individual components of the department being “viable on its own”. This statement mirrors the lack of value historically ascribed to these objects through their various classifications. (Similar worries surfaced when I read about the V&A’s plan to create one department to cover “sub-Saharan Africa and African diaspora art, design and performance and the Asian collections“.)

Durrans saw the shedding of the word ethnographic from the museum’s departmental structure as a way of allowing the collection to “aspire” to a higher profile. In a 2004 article, he argued that, in future, anthropologic study would be emphasised cross-departmentally, with a Centre for Anthropology being shared across the museum’s collections. This hasn’t been fully realised, and today the Anthropology Library and Research Centre is listed on the British Museum’s website as a facility of the AOA Department, is not mentioned in relation to any other department, and specifically “offers access to extensive information around ethnographic collections”. It is clear that the ethnographic taxonomy runs much deeper than a simple departmental name.

The continent of Africa has been in contact and conversation with other parts of the world since time immemorial and this should be reflected in the displays. While it was great to read on the museum’s website that “every department in the Museum includes African objects in its collections”, I hope a future gallery layout might emphasise these connections rather than hiding the African collection away.

Undoing the assumptions and challenging the histories which are so closely woven into the fabric of the museum and its structures is no mean feat. Departmental structures and object taxonomies might seem like small fry, but museums need to carefully consider how these directly impact the way visitors encounter the cultures that are on display. I question whether a two-year project is really enough to address structures that have been centuries in the making.

Selected bibliography:

(Additional news articles and websites have been linked in the text itself)

BOUQUET, Mary, Museums: A Visual Anthropology (London: Berg, 2012)

THE BRITISH MUSEUM, A Guide to the Exhibition Galleries of the British Museum (London: Woodfall and Kinder, 1879)

CHAMBERS, Neil, ‘Joseph Banks, the British Museum and Collections in the Age of Empire’ in Enlightening the British: Knowledge, Discovery and the Museum in the Eighteenth Century (London: The British Museum Press, 2003), pp. 99-113

DIXON, Carol Ann, ‘The ‘othering’ of Africa and its diasporas in Western museum practices’ (Doctor of Philosophy, University of Sheffield, 2016)

DURRANS, Brian, ‘Anthropology and the British Museum: On the Planned Abolition of the Department of Ethnography’, Anthropology Today 20, 4 (2004), 23-24

GREENE, Graham, Preface to Africa: Arts and Cultures ed. by John Mack (London: The British Museum Press, 2000), pp. 6-7

JONES, Peter Murray, ‘A preliminary check-list of Sir Hans Sloane’s catalogues’, The Electronic British Library Journal (1988), 195-222 (bl.uk/eblj/1988articles/pdf/article3.pdf) [Accessed: 27/03/2021]

SPRING, Christopher James, ‘A Way of Life: Considering and Curating the Sainsbury African Galleries’ (Doctorate in Professional Studies by Public Works, Middlesex University, 2015)

WILSON, David M., The British Museum: A History (London: The British Museum Press, 2002)

WILSON, David M. ed., The Collections of the British Museum (London: The British Museum Press, 1989)