Notes on Growth

I was swept into September like a piece of driftwood being rocked up onto safe, sandy shores. I’ve never stopped operating in academic years and September has always brought with it a sense of calm. New beginnings often have that effect on me – stresses and worries wiped away, or at least obscured, by promises of abundant time and expectations not yet tempered or disappointed. I felt full with energy and excited about writing something new on the theme of growth, my mind buzzing with ideas.

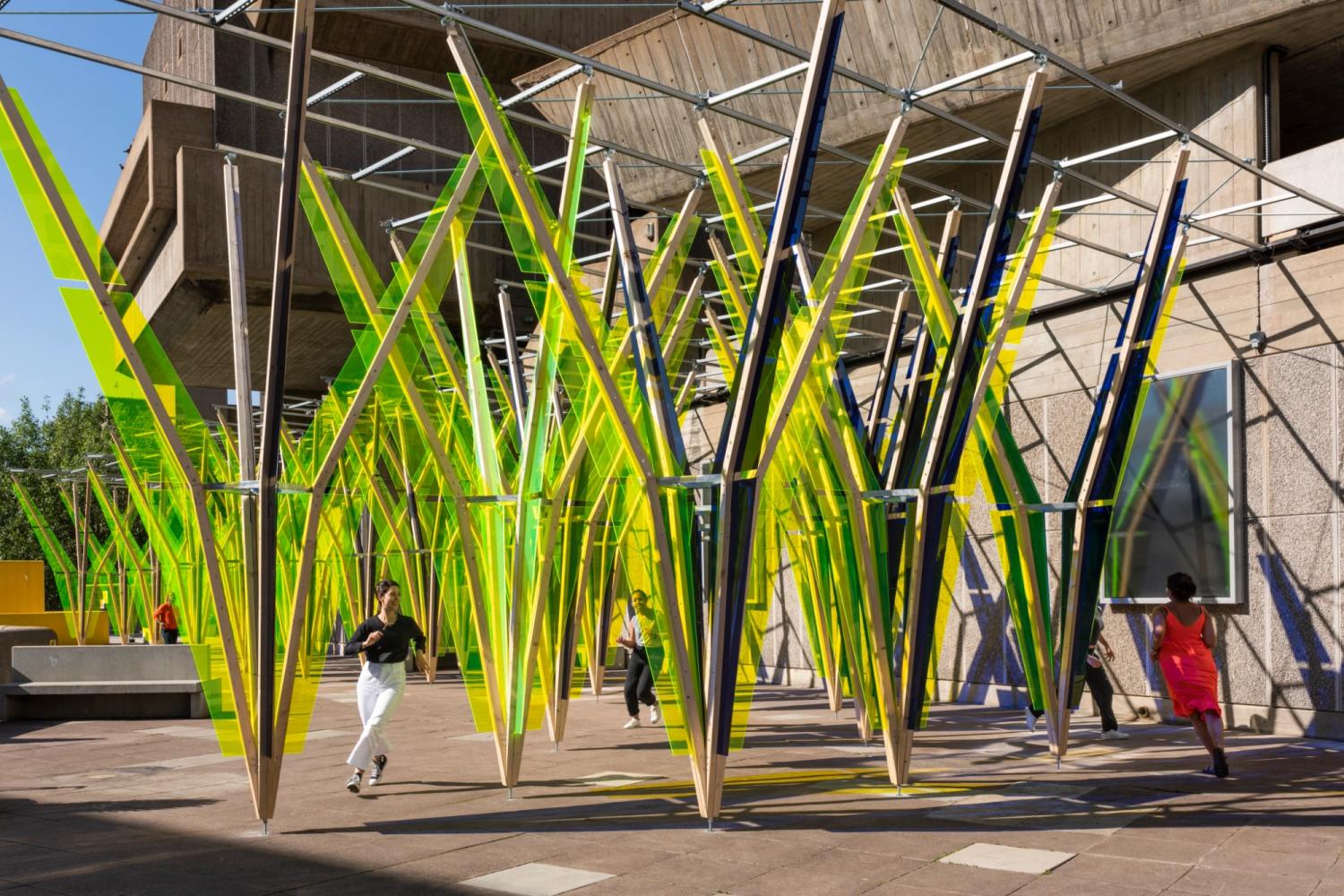

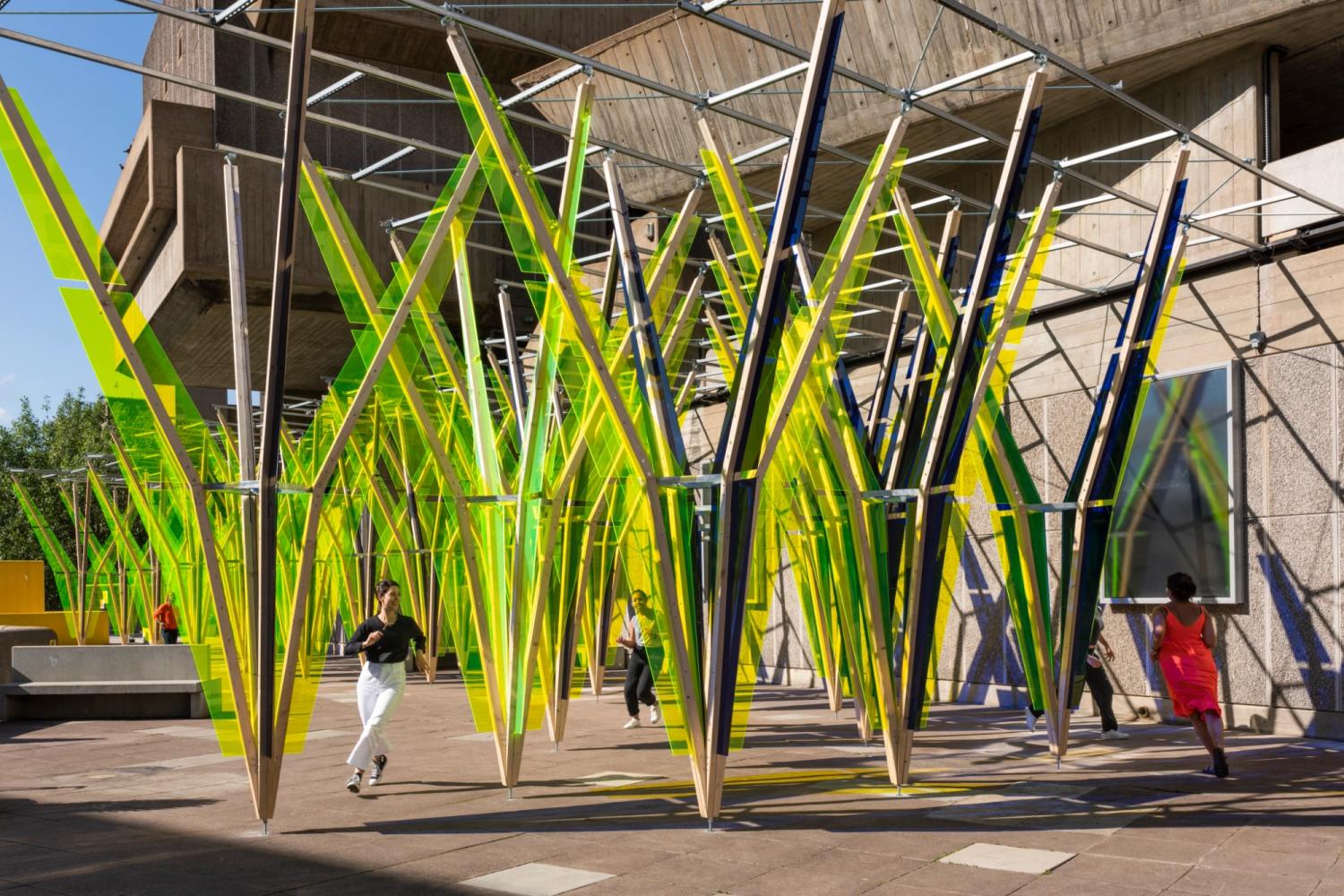

I spoke to the artist Jyll Bradley about her outdoor installation The Hop, which I curated at the Hayward Gallery. An interactive pavilion, The Hop evokes the geometries of a Kentish hop garden, where the vines are strung up on coir wires to expose the crop to the maximum amount of sunlight. Jyll sees these structures as anthropomorphic, recalling a chorus of women with their arms stretched up and out to embrace the sky, hands just touching. For over a century, thousands of women and children travelled from London down to Kent to help bring in the hop harvest, forming a new sense of community with other Londoners in rural England.

Jyll mentioned her interest in Stonehenge and it struck me how monuments don’t normally grow physically but they shift and change and grow in meaning. While Jyll’s sculptures have often been temporary visitors to sites around the UK (and further afield), her work Green/Light (For M.R.) has been rooted in Folkestone for eight years. And people want to keep it there longer. What does it mean for a temporary intervention to become permanent architecture, to fuse with a place and seep into its identity?

I sat with Jyll in another temporary intervention made permanent, the roof garden of the Queen Elizabeth Hall. Bees and wasps and other pollinators buzzed in the air. Ants made paths of my skin. The garden is thriving and blooming, breaking out of its wooden planter bounds and transforming the grey concrete slabs of brutalist architecture. Here in the garden was growth and change, of meaning and environment. The Hop, meanwhile, was not actually alive, but it too grew in the afternoon light: colourful shadows creeping up the wall and new patterns cast by a sun fading into autumn.

Walking home that day, I called my mum and while we were on the phone my dad got the news that his cancer has returned. Suddenly, my mind was full of a very different kind of growth. Growth that cuts beneath me, severing my roots. I don’t know how to deal with this growth because it is something I cannot see and I struggle to understand. We now wait for more news with a kind of patient acceptance that makes me angry. And after we finish waiting, there will be more waiting still. Waiting for news about growth: where, how much, how bad.

In Jyll’s work, growth is something that brings communities together. Her works create spaces for creative and spiritual growth, spaces that both contain and open up to the sky, that are generous and secure. I’ve loved watching how children interact with this kind of space, like a playground full of obstacles and opportunities. An environment that makes almost every child spontaneously start running, as if the only way to experience it is at speed. The Hop gives purpose even to gaps and passageways, spaces that the work creates but does not occupy.

My dad created a temporary community through Whatsapp a few months ago. While recovering from surgery last year, he decided that he was going to cycle the length of the UK: 874 miles from Land’s End to John O’Groats. Only seven or so months later, he was on his way, traversing the Cornish hills and sharing his live location on a new Whatsapp group that brought together family and friends. Now, I know big group chats and their constant notifications can be irritating. But, for me, this was a place of complete joy where people sent encouraging and supportive messages: stupid gifs, videos of them cheering in their garden, sympathy for sore bums. Members of the group went out to meet him, to cycle part of the day with him, or take him out for lunch, and shared all of this through the group chat. We all breathed a collective sigh of relief when my cousin Tom joined him for the gruelling last two days in snowy Scotland.

Amazingly, he completed the whole ride in only seven days and – after all the congratulatory messages – promptly removed everyone from the group. The group still exists, not physically growing, but a monument to my dad’s achievement and to the support and kindness of the people he knows. A disparate group of people, many of whom have never met, who were brought together in this virtual space by my dad for just over a week.

Through all this, I think I am developing a healthy ambivalence to growth. For much of my life I have been obsessed with an idea of personal growth. I kept diaries from the age of 14 to 22 which are full of me wanting to be a ‘better person’: to bitch less, read more, eat and maybe talk less, make people like me more, to push myself to be better and to love myself as I am. The way I think about growth has always been to look to the future, rather than to create space in the present. When I constantly look to future growth, I am left with that same angry impatience I feel as I wait for news about my dad’s health and wait for future versions of me that will never exist.

Instead, I like the idea of growth like a hop plant, stretching its tendrils out into the present world and connecting with others. But also growth that reaches down into the earth. Growth that is rooted, and knowledge that is deep and earthy, satisfying and slow.